|

A recent story on NPR discussed four picture books that were banned when they were published that Americans would now see as innocuous. All four contained images of racial integration. Strangely, even though the illustrations of black and white children playing together were what so enraged Jim Crow–era community leaders, the article failed to mention the illustrators of these four books. I decided to do a little research. I had to remind myself that miscegenation laws were not overturned by the Supreme Court until 1967, and some city swimming pools were not forced to integrate until the 1970s. These illustrators were all leaders of cultural change. While we can’t go back in time to ask them about their thoughts while illustrating these controversial books, I believe they were all making conscious decisions to visually integrate their books. They were probably highly sensitive to the fact that they risked being censored, and they chose to make these books because they believed in the power of illustration to change the hearts and minds of their readers (both children and adults). Here is a little bit about the illustrators of the four books profiled by NPR, and a bonus new picture book about Loving v. Virginia. Black and White, 1944 Charles G. Shaw was a renowned American abstract painter, and author/illustrator of the classic It Looked Like Spilt Milk. He collaborated with Margaret Wise Brown on The Nosy Bookseries. The text of the book specifies that the characters are a black man and a black woman. The man loves only black things until he sees snow, then it snows and leaves a white snow lady in his yard. They fall in love and get married. Swimming Hole, 1950 Louis Darling, Jr. was an American illustrator, writer, and environmentalist, best known for illustrating the Henry Huggins series and other children’s books written by Beverly Cleary. He and his wife Lois provided illustrations for the first edition of Silent Spring by Rachel Carson. The plot of this book involves a white boy moving into a new neighborhood where some of the neighbors are black. The boy realizes that “his sunburn is more of a problem” than integrated swimming. First Book of Fishing, 1952 Edwin Herron was an illustrator of science books for kids and a political cartoonist under a pen name for a socialist journal that published from the 60s-late 80s. Since this was a nonfiction book, Edwin Herron’s choice to visually integrate the children pictured in the book was most likely his own. The Rabbits’ Wedding, 1958 Garth Williams was the illustrator of Stuart Little, Charlotte’s Web, and the Little House series. The text of The Rabbits’ Wedding refers to the main characters as “the little white rabbit” and “the little black rabbit;” they are illustrated as fairly realistic wild rabbits who decide to put flowers behind their ears and get married so they can be together always. Williams said about this book that he “was completely unaware that animals with white fur, such as white polar bears and white dogs and white rabbits, were considered blood relations of white beings. I was only aware that a white horse next to a black horse looks very picturesque,” and that his story was not written for adults, who “will not understand it, because it is only about a soft furry love and has no hidden message of hate.” The Case for Loving, 2015

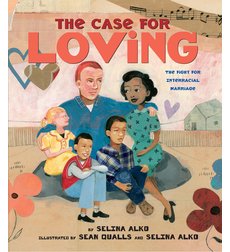

The Case for Loving is a narrative nonfiction picture book that tells the story of the real family who won the Supreme Court case Loving v. Virginia. I’m not sure if it is the first picture book since Williams wrote about bunny love in 1958 to address interracial marriage, but it is definitely a landmark picture book. The Case for Loving: The Fight for Interracial Marriage by Selina Alko (Author, Illustrator),and Sean Qualls (Illustrator) (The two are a husband/wife team, which is a warm and fuzzy as bunny love.) Comments are closed.

|

AuthorJeanette Bradley loves penguins, art, and chocolate, though not all at once. Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed